Is 9Marks (Leeman) Shaking on Sola Scriptura?

Introduction

The intention of this article is not to make a personal attack on Jonathan Leeman. For many reasons, such as his willingness to engage in conversation with those whom he sharply disagrees with (consider his appearance on CrossPolitic), I do not want to characterise him as a political actor, or even create doubt about his personal commitment to Jesus Christ as his Saviour. I would not have us regard Leeman as an enemy, but warn him as a brother. Yet notwithstanding this, words have meaning. What he has written as the editorial director of 9Marks, influences the churches, and he is responsible for it.

Secondly, I think it entirely fair to represent Leeman’s position as that of 9Marks as a whole,

given his position as editorial director:

However, if anyone can point to a senior member of the

9Marks team

who disagrees with Leeman’s perspective, I will happily retract the charge in the title.

However, if anyone can point to a senior member of the

9Marks team

who disagrees with Leeman’s perspective, I will happily retract the charge in the title.

We shall begin by considering the definition of Scripture’s sufficiency which 9Marks has offered in the past, as a backdrop for looking at the view currently being put forward by Leeman. It is critical to see that because the change in views is implicit, he will not come out and say “the Scripture is unable to guide us here” in so many words. Such a statement would require that he be self-conscious of the change, when I regard it as implicit and unconscious, though culpable. After this we will consider Leeman’s present views regarding how the church is to make decisions with respect to COVID-19 and governmental regulation.

Scripture’s sufficiency as defined by 9Marks

(I am using the term sola scriptura in the title as including within itself the sufficiency of Scripture.)

In Episode 52 of Pastors’ Talk, Leeman and Dever discuss the topic of the sufficiency of Scripture. Leeman begins by asking Dever to provide a definition:

That God has revealed himself in his word, giving us everything we need to know for life, and knowing him, and following him.

(Mark Dever)

However, unsatisfied with the potential vagueness of the term “life”, Leeman proceeds to quote the following from Grudem:

…sufficiency of Scripture means that Scripture contains all the words of God he intended his people to have at each stage of redemptive history, and that it now contains all the words of God we need for salvation, for trusting him perfectly, and for obeying him perfectly.

(Wayne Grudem, as quoted by Leeman, emphasis mine)

It is crucial that we understand the view they are uttering here. It is not merely that the Bible is helpful or informative. Neither is it only for the individual believer struggling to know God’s will. Rather, they insist that the Bible is “all the words of God he intended”—i.e. nothing beyond the Scripture is intended or needed, and moreover, all that he intended for “his people” and it now contains “all the words of God we need”. Thus the Bible is understood by 9Marks, by Dever and Leeman, as all that the church needs to obey God perfectly. Consider the following quotes from the same podcast (all Leeman, his emphasis):

…one of the tremendous joys of a knowledge of the doctrine of the sufficiency of Scripture is that [sic] sometimes we feel like, “Oh my gosh! Why doesn’t the Bible say more about this.” “I really wish God would’ve been clearer on that.” But this doctrine assures us, “No, you have what you need here.”

…and it’s not as if God’s like, “I love you but I’m not going to tell you what you need to know; I’m just gonna hold it back”—that’s ridiculous.

And what we don’t know we don’t need to know. [Cites Deut. 29:29]

There may be things that the Bible has not revealed, but when it comes to “salvation” to “trusting him perfectly” or to “obeying him perfectly” it is all that we need. This, and only this, is the Protestant doctrine of the sufficiency of Holy Scripture, and this is the view which Dever and Leeman claim to hold.

Today, I mean to fasten unyieldingly to the phrase for obeying him perfectly: according to Jonathan Leeman, to Mark Dever, and to 9Marks, at least on 15 May 2018, Scripture contains all the words of God we need for obeying God perfectly. We shall see whether this conviction has lasted the storm of these three short years, or if, to their shame and our dismay, it has been modified by some pragmatic and humanistic considerations.

We shall now consider the views that Leeman has been putting forward regarding the church and how she may know the Lord’s will, in the context of the COVID-19 crisis.

Unguided human reason considered harmful

It is a dangerous thing for fallen creatures to reason and philosophise. It is necessary, but always dangerous. For this reason we are warned by the apostles, “learn by us not to go beyond what is written” (1 Cor. 4:6). Ideas are most damaging to the church when they appear to have been deduced by good and necessary consequence from the word of God.

This is a danger to which we are all open. None of us is above the constant need to test by the written word every thought that arises in our minds. All of us must depend on the guidance of the “Holy Spirit speaking in the Scripture” and upon the “infallible rule of interpretation of Scripture” which is “the Scripture itself”. The moment we begin to love and trust our systems more than we love and trust the solemn voice of the prophets, “Thus saith the Lord”, we risk landing ourselves in the “irreverent babble and contradictions of what is falsely called ‘knowledge’” about which Paul warns so sternly (1 Tim. 6:20).1

Turn to Leeman’s recent writing on the COVID-19 controversy and you will find a sudden illustration of the fickleness of human reason. In a piece titled When Should Churches Reject Governmental Guidelines on Gathering and Engage in Civil Disobedience? published in May last year, he explains why (in his opinion) the question is difficult. The issue for us to focus on is the source of his position. Is Leeman reasoning with Biblical categories or those from political science? Are his assumptions controlled by Scripture or by human reason and “common sense”?

“jurisdictional overlap”

Leeman begins (emphasis mine):

Here’s why it’s a difficult topic from a biblical perspective: both the government and our churches have a legitimate biblical claim on the territory of gatherings. You might call it jurisdictional overlap.

Simple Christians may be pardoned for their naivete if they expected an exegetical analysis of the question at hand. Since Leeman is allegedly writing “from a biblical perspective”, we may have hoped he would look to the written word to ask (i) whether the church is commanded to gather and (ii) the circumstances under which this command does not apply and finally, (iii) whether we are in such a circumstance. This would indeed be biblical procedure. Instead, however, Leeman hurls at us an unfamiliar term, jurisdictional overlap.

“Brother”, some of us may want to ask Leeman, “what is this strange word, jurisdictional overlap? And is it found on the pages of Scripture?” Now at this point it may be objected that there are many extra-biblical, theological terms which Christians have used through the centuries to capture Scriptural concepts, such as trinity, sacrament and the like. So let us read on and see if Leeman is advancing the church’s knowledge in a manner analogous to Tertullian’s use of trinity, let us see if jurisdictional overlap is nothing but a new name for a concept found in the oracles of God.

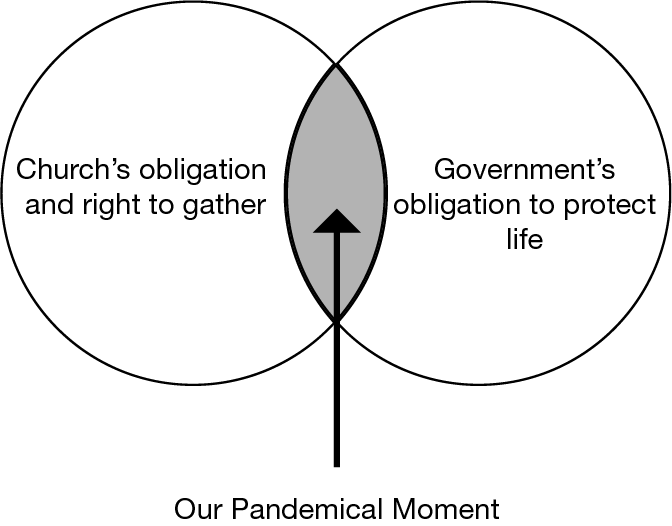

Governments possess authority, if for no other reason, then to preserve human life (see Gen. 9:5–6). They are obligated by God to do so. If temporarily banning all gatherings of a certain size accomplishes that end, they should.

At the same time, churches possess a right to gather, arguably as a property of a natural right to freely assemble, certainly as the religious right to assemble. Our vertical obligation to worship God as churches creates that horizontal right with respect to other people and our governments.

So picture two overlapping circles, one representing the church’s jurisdictional obligation and right to gather, the other representing the government’s jurisdictional obligation to protect life. Our pandemical moment places us smack dab in the middle of where these jurisdictions overlap. That, as I said, is what makes this moment difficult.

(The illustration above is taken from the article.)

The first observation to be made may appear to be a minor one. Leeman characterises the government’s authority as “to preserve human life” while citing Gen. 9:5–6. Yet this text says nothing explicitly about preserving human life, indeed on the contrary, it is the divine institution of capital punishment for murderers:

And for your lifeblood I will require a reckoning: from every beast I will require it and from man. From his fellow man I will require a reckoning for the life of man. Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed, for God made man in his own image.

We are immediately led then to suspicion regarding this supposed overlap of authority, since the first text which Leeman offers in its defense rests upon the unargued assumption that the government bears not the sword but the stethoscope, that it is ordained not as a terror to bad conduct and as “an avenger who carries out God’s wrath on the wrongdoer” (Rom. 13:4) but as a preserver of human life. In effect, this is to turn the state into the institution of healthcare, rather than the institution of civil justice, and who can doubt that this is what most Christians who defend the COVID-19 restrictions believe—but let us not get ahead of ourselves.

The second observation is that in Leeman’s mind, the jurisdictional obligation of both the government and the church is to God. He says of the former that “they are obligated by God” to “preserve human life”, of the latter he speaks of “vertical obligation to worship God” and “jurisdictional obligation and right to gather”. I think there can be no doubt that the obligation is to God, given this context.

This is important because divine obligation can only be imposed by revelation. And if there is an overlap of obligation in which two institutions with legitimate authority may be pitted against each other, the question immediately arises, how can this be, if God’s commandments are consistent? Or to ask the question from a different angle, in pitting two divinely-authorized institutions against one another, is Leeman, if unwittingly, charging God’s word with contradiction?

We shall have to wait for later in his article before Leeman clarifies his view on this point. He proceeds now to argue that in this jurisdictional overlap, the rule of the state should precede that of the church.

“First, peace and safety. Then church work. At least typically.”

If the government has a reasonable argument to ban every kind of gathering in order to protect life, then churches should act the part of dutiful citizens and obey the government. They shouldn’t just “go along with the government by our own free will,” as a friend of mine put it. They should positively submit. Submitting to it is to submitting to God (Rom. 13:1–2).

Why should the government’s authority come first? Because preserving life now allows for the freedom to gather later. You cannot gather as a church if you’re dead. Paul therefore tells us to pray for kings, and to lead and peaceful and quiet lives so that people can be saved (1 Tim. 2:1–4). First, peace and safety. Then church work. At least typically.

We begin now to see Leeman’s priorities, i.e. “at least typically”. He considers it within the government’s authority, when it “has a reasonable argument”, to “ban every kind of gathering”, including the church. At this point I would raise a red flag. Is this something he has even began to demonstrate biblically? The church is to “positively submit”, to submit as unto God, he says, referring to Romans 13. Does this text say anything about the government’s right to ban church gatherings? Doesn’t it instead speak about its obligation to punish evildoers? Where does healthcare even enter into consideration there?

Yet what follows is even more troubling. “You cannot gather as a church if you’re dead”, says Leeman. I am afraid our brother is suffering from a woefully under-realised eschatology. It is true that the saints of old cried to God, “Sheol does not thank you…The living, the living, he thanks you, as I do this day” (Isa. 38:18) and “Is your steadfast love declared in the grave, or your faithfulness in Abaddon?” (Ps. 88:11). But is this the language of believers living under the reign of the risen Lord, who says to them,

Fear not, I am the first and the last, and the living one. I died, and behold I am alive forevermore, and I have the keys of Death and Hades.

(Rev. 1:17–18)

David asked, “What man can live and never see death? Who can deliver his soul from the power of Sheol?” (Ps. 89:48) and here the Son of David answers upon his resurrection “I am alive forevermore, I have the keys of Death and Hades”. We have a God, indeed, a man, “who knows his way out of the grave”.

For none of us lives to himself, and none of us dies to himself. For if we live, we live to the Lord, and if we die, we die to the Lord. So then, whether we live or whether we die, we are the Lord’s. For to this end Christ died and lived again, that he might be Lord both of the dead and of the living.

(Rom. 14:7–9)

This, and not “first, peace and safety”, is the cry of the New Testament. “First, peace and safety”, even if qualified by “at least typically”, is the cry of human pragmatism. It is cowardice and ungodly fear of things that can destroy the body but never touch the soul. Let us see how Leeman’s priorities line up with the Bible’s.

Leeman says, “First, peace and safety”—but Paul says “to live is Christ, to die is gain”—”at least typically”; but Paul says “now as always Christ will be honored in my body, whether by life or by death” (Phil. 1:20–21).

Leeman says, “First, peace and safety”—but Peter says “rejoice insofar as you share in Christ’s sufferings, that you may also rejoice and be glad when his glory is revealed”; “at least typically”—but Peter says “do not be surprised at the fiery trial…as though something strange were happening” (1 Peter 4:12–13).

Leeman says, “First, peace and safety…at least typically”—but John speaks of himself as “your brother and partner in the tribulation and the kingdom and the patient endurance that are in Jesus” (Rev. 1:9).

Leeman says, “First, peace and safety…at least typically”—but Jesus says “In this world you will have tribulation. But take heart; I have overcome the world” (Joh. 16:33)

Leeman says, “First, peace and safety…at least typically”—but an apostle says, “It is for discipline that you have to endure. God is treating you as sons. For what son is there whom his father does not discipline?” (Heb. 12:8)

I seriously doubt that Leeman has realised how far his sentiment is from that in Scripture. “First, peace and safety. Then church work.”—tell that to Paul:

Are they servants of Christ? I am a better one—I am talking like a madman—with far greater labors, far more imprisonments, with countless beatings, and often near death. Five times I received at the hands of the Jews the forty lashes less one. Three times I was beaten with rods. Once I was stoned. Three times I was shipwrecked; a night and a day I was adrift at sea; on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from robbers, danger from my own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brothers; in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, in hunger and thirst, often without food, in cold and exposure. And, apart from other things, there is the daily pressure on me of my anxiety for all the churches.

(2 Cor. 11:23–28, my emphasis)

For Paul, this is what characterises “servants of Christ”. Yet it may seem in this context the false teachers of Paul’s day knew better than Leeman what “church work” was about, since they competed with Paul not for “peace and safety” but for having endured more suffering. The sentiment of the believer calibrated to Scripture is to glory in sharing in Christ’s suffering:

For he was crucified in weakness, but lives by the power of God. For we also are weak in him, but in dealing with you we will live with him by the power of God.

(2 Cor. 13:4)

“First, peace and safety. Then church work.” “You cannot gather as a church if you’re dead.” But the Bible tells us:

…you have come to Mount Zion and to the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem, and to innumerable angels in festal gathering, and to the assembly of the firstborn who are enrolled in heaven, and to God, the judge of all, and to the spirits of the righteous made perfect, and to Jesus, the mediator of a new covenant, and to the sprinkled blood that speaks a better word than the blood of Abel.

(Heb. 12:22–24)

Are we to understand that there is no church in heaven?

But sadly, we have not yet come to the bottom of Leeman’s delusion.

“no black and white answer”

We come to the heart of Leeman’s position when he asks whether the church may engage in civil disobedience. (The emphasis below is Leeman’s.)

If you were paying close attention, however, you caught my two qualifications.

First, the government has to have a reasonable argument. A totalitarian state which completely banishes the freedom of assembly probably doesn’t have such a reasonable argument. One ground for civil disobedience, then, would be when it’s overwhelmingly obvious to good sense and reason that the government has no legitimate basis for banning gatherings.

To be sure, determining what’s a reasonable argument or a legitimate basis requires case-by-case judgments, and Christians might disagree. Stopping a pandemic which kills more than 50,000 U.S. citizens within a month strikes me as pretty reasonable.

Second, the government cannot single out religious groups. If it allows sporting events and concerts and political conventions to meet, then it should not forbid churches from meeting. If a government does single out churches, again, then the church may have biblical warrant to disobey.

Again, naive readers may be forgiven for thinking those governments totalitarian which banned gathering in churches or in some cases permitted gathering while forbidding singing, while at the same time permitting thousands to gather (and riot and loot and destroy property) for protests. But let us not get sidetracked with a debate for another day.2 Leeman continues (my emphasis):

One pastor asked me what he should do if he disagreed with the government’s assessment of what is reasonable. Should they meet anyway? In the final analysis, there is no black and white answer when jurisdictions overlap that we can look up in a book of case-law. The definition of submission is deferring to another’s judgment, rather than your own. Still, every authority on earth is relative. No authority is absolute except God’s, which means we never surrender judgment to another human entirely, and therefore we have to ask God for wisdom and rely on him in these tough cases of jurisdictional overlap.

So a pastor asks 9Marks whether the church should meet in defiance of government regulations and the response is “In the final analysis, there is no black and white answer when jurisdictions overlap that we can look up in a book of case-law”. No book? No book that the church can consult to know whether it is bound to meet? I thought we had a book, the Bible? Surely we’re misunderstanding Leeman? Surely “we have to ask God for wisdom” is a reference to consulting his written revelation, which contains all the words of God we need for obeying God perfectly?

Leeman again (my emphasis):

As such, the ultimate test comes on Judgment Day. So if you’re tempted to disobey, ask yourself, do you believe God will vindicate your disobedience by saying to you on the Last Day, “Yes, you were correct, pastor, to lead a congregation to overlook what I said in Romans 13 because the government was asking you to sin”? Those are high stakes. That should make you nervous.

But how, pray tell, is the pastor to know if God will vindicate his obedience? How, since “the secret things belong to God” and today (so far) is not judgement day? Leeman leaves him “nervous” and with “no black and white answer”, rather than with a word from the Scripture. Notice also that he is not saying that there are circumstances in which Romans 13 does not apply and that therefore the believer is free, such as when commanded to sin by the government. Rather, he is saying that due to a jurisdictional overlap, the pastor may disobey the divinely-sanctioned authority of the government.

Thus the article concludes with some soft words about loving our neighbors and preserving our witness by submitting to an authority when we do not know if we are obeying God. But Leeman addresses this same point again in an article on the church and mask mandates from September of this year. Perhaps he will at last tell us that the Bible is sufficient to answer us? Sadly, he does the precise opposite (my emphasis):

…the ultimate theological answer is, everyone who will stand before God and account for their obedience both to church and state must decide. He has established both authorities. To submit to both is to submit to him. That means, most conflicts in these areas of overlapping jurisdiction, where you can find a Bible verse to support each side, won’t finally be resolved until Judgment Day. God alone will adjudicate them perfectly then. In the meantime, we ask God for wisdom and make our best judgments.

What a great change. Yesterday he says we have “all we need for obeying God perfectly” but today he says we wait “until Judgement Day” when “God alone will adjudicate them perfectly”.

“our best judgements”

It is hard to escape the inference that by jurisdictional overlap Leeman means nothing other than a contradiction in the revealed will of God. This is why we have to wait for judgement day, and he openly admits “you can find a Bible verse to support each side”. Note that he doesn’t say “you can find a Bible verse that seems to support each side”—note that his whole argument and position rests on the “conflicts in these areas of overlapping jurisdiction”.

He may not intend to, but he has with his philosophy annihilated the Scripture’s sufficiency and authority, and left us “to ask God for wisdom” and to “make our best judgements”. And unless Leeman believes that God is still revealing his word authoritatively to the church, he has left us to “our best judgements”.

In closing I will re-iterate what I said at the beginning because the words I have used may appear harsh. Indeed, it may seem to some that I have judged Leeman’s writing in the worst possible light. I speak of “shaking” in the title because I believe this to be an implicit and unconscious change. I am not the “judge of all the earth” and I do not accuse Leeman (or anyone else in 9Marks) of knowingly and explicitly abandoning sola scriptura. But if I have shown Leeman’s views to undermine the authority and sufficiency of Scripture—I am bound in the fear of the Lord to call it what it is, an affront to the majesty and clarity of God’s revelation. Shall we follow Leeman into his political-scientific world with no “black and white” answers? Shall we rely on “our best judgements” rather than the written word applied to today?

For those who believe that the will of God “is good and acceptable and perfect” (Rom. 12:2), Leeman’s position needs no refutation. Indeed, its very statement is its own refutation. I will therefore not venture into the work of refuting it, which seems most vain and unnecessary.

The Bible is the Church’s book of case-law, and every other kind of law, its only and sufficient rule of faith and practice. Let us instead call our brothers in 9Marks to repentance from this drift towards theological liberalism: for the meaning of Scripture “is not manifold, but one”.

Footnotes

-

In citing this passage it may appear that I am charging Leeman with “swerving from the faith”, which is the next thing Paul mentions. This is not my intention, but rather, to warn him and his readers that to proceed in the direction that his article shows he is taking may lead there. ↩

-

Leeman provides no context for this figure. He sees it unnecessary to use the CDC’s own admissions that the vast, vast majority of COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. include on average 4.0 serious comorbidities. (That number is above 94%, as of today.) Many more objections could be registered against Leeman’s superficial quotation of these figures. Perhaps we should give him grace since this was May of last year, yet in this article from September 2021 he reasons in exactly the same way. ↩